Building With Rust

I’ve been developing software professionally for over 10 years now. In that time, I’ve mostly focused on the backend (with the occasional daliance with WebGL, JS, TypeScript and that entire mess of an ecosystem).

My go-to languages in that time have been Java and Golang. Golang is simple, easy to get started with, and is incredibly convenient to deploy. I’ve built many projects with Golang that are never meant to grow huge, but to do one thing really well. Some examples are

- A library and SDK for parsing the structure of Java’s compiled classfile format

- A minimal TUI for browsing + DVR functionality on traffic cameras

- A pipeline for minifying software artifacts to be transported to airgapped envs

Go was an excellent fit for all of these projects because it’s simple to get started with, builds a single statically linked binary, has built-in cross-compilation support, and overall easier to maintain. There’s a lot of Golang code in the internet so it’s also useful to get a sense of best practices.

For most of the past decade, though, everything I’ve shipped to prod for my work has been in Java.

I love Java.

More specifically, I love the Java Virtual Machine. It’s an incredible piece of technology, and was ahead of its time in many ways:

- It’s based on Smalltalk and earlier OOP languages, and leans hard into the runtime configurability aspect. Most interesting pieces of Java code and libraries make use of Reflection and runtime behavior.

- The JVM will JIT-compile bytecode to code for your specific architecture, including features like SIMD in limited cases

- The JVM has excellent interop with native code, and frameworks like JNA and java-cpp-presets have off-the-shelf integrations with nearly every popular C/C++ framework.

- Because of the 30 years of compiler expertise that’s gone into Java, first under Sun and then under Oracle, Java is fast. It also supports code generation and compilation at runtime through the JVM Compiler Interface. For many years, Apache Spark’s “compiler” for DataFrames was just generating specific Java code of pipelined operations, and then just letting the JIT optimizer make the code even speedier.

- The JVM supports many languages with greater feature richness than Java, including Kotlin and Scala. Personally, I find the drawbacks of both of those languages enough where I’d prefer to use Java with a set of excellent libraries out of the box.

- The JVM has far and away the best observability tooling of any software platform in existence. I am fully convinced of this. Both first-party

tools such as

jstackand JFR allow examining complex server applications in-situ, while they’re running, with minimal performance overhead. (1-2%). Third party tools like YourKit and the IntelliJ (the paid one’s) builtin Profiler functionality offer rich analysis of flamegraphs, memory traces and native code.

Given this love, I’d always imagined myself being glued to Java for the rest of my professional career. I’ve invested a lot of my effort into becoming comfortable with the critical parts of running Java in production, and when you’re waking up at 2am to fix a SEV0, the last thing you want is to have to relearn the tools.

…Rust⌗

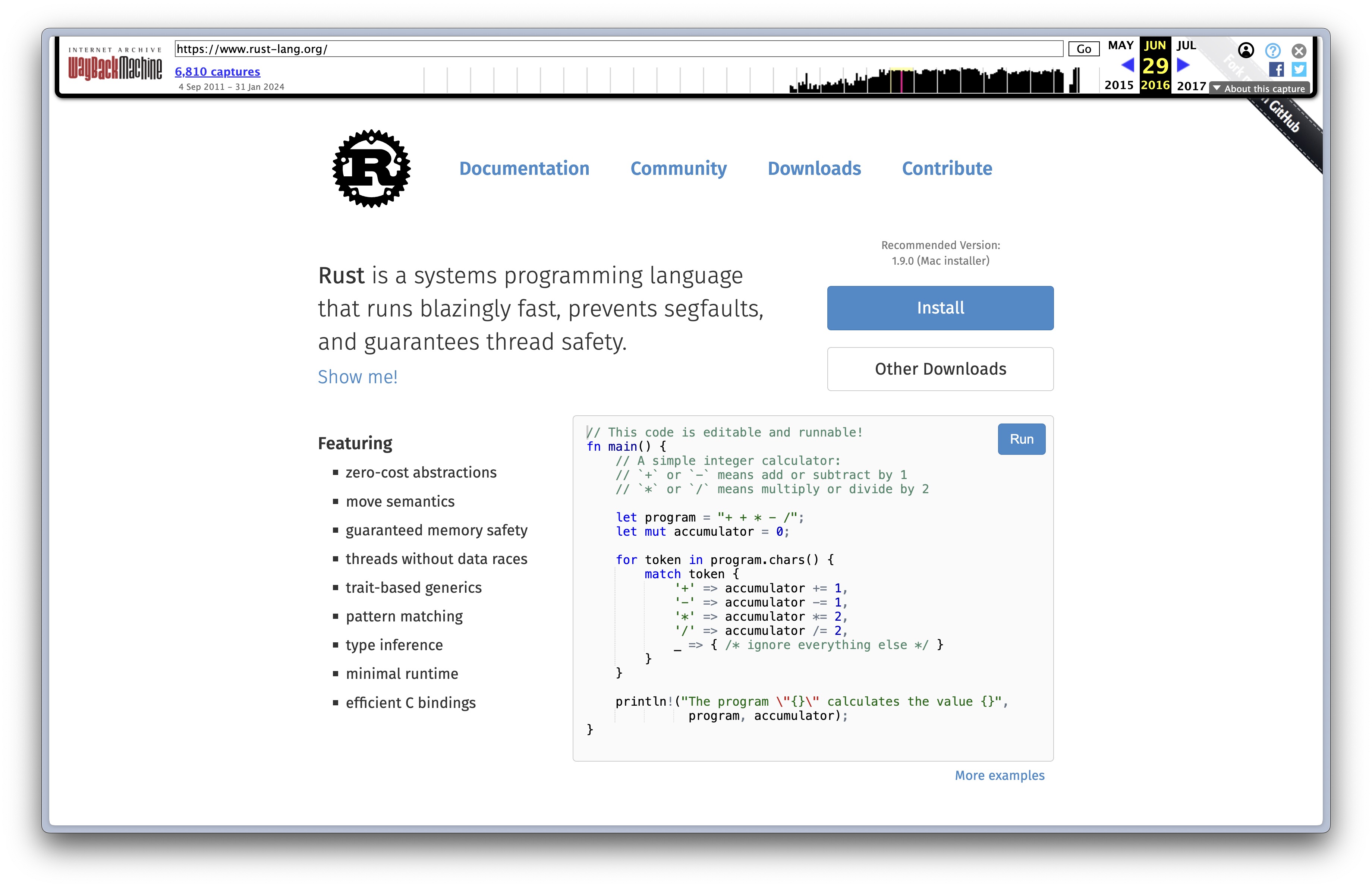

I first encountered Rust in 2016. At the time I was really excited about compilers and functional programming concepts. I wrote Haskell and Emacs Lisp for fun little personal automation projects. I loved Scala, and I could tell you back then about Functors and Monads and how they were the best way to build composable software (I knew nothing about the real world back then).

I was also really interested in systems programming as my major was focused on operating systems and distributed systems, and at the time Rust was still billing itself as a Safe Systems Programming language to compete with C.

I saw the buzz around Rust and figured I’d dive in.

I fell flat on my face. I spent a few days trying to build something relatively simple: a clone of a Redis service using a simple key-value collections interface.

I ran into a bunch of issues upfront trying to get productive with the language:

- The compiler was extremely verbose, and error messages were hard to understand. It used lots of terms that I was not familiar with like “lifetimes” and “borrows” and “moves”.

- Seemingly small changes in the program, like including or not including a reference type, would cause the compiler to throw these very opaque errors.

- I had gotten used to being able to create pointers to data structures and pass them into threadpools to parallelize work. I don’t quite remember what went wrong here but I just remember giving up.

Though I managed to eek out a bit of Rust code, I couldn’t figure out how to build an entire application with it, and so I put it down.

4 years later⌗

I’d been observing Rust in the time since my first brush with it. It was really taking off! I don’t think I saw anyone I knew building their entire stack on it, but a few really interesting projects had popped up in the meantime:

- tokio and async-await more generally entered the language, creating a new set of opinions in the language for building full-stack performance-sensitive applications that fully utilize the hardware.

- BurntSushi’s ripgrep was a tool I used everyday, and the fact that he was able to make it so fast using Rust was pretty exciting.

- Tonic became a leading framework for building services with gRPC. gRPC was something I used increasingly for work to build APIs and integrate software from third-party vendors, so I took note of it.

Circa 2020, I ended up at work needing to build something that would run on a satellite. The tough part was that the satellite was already in orbit, and we had to get the software up there.

Our company was almost entirely a Java shop, and we wanted to demo that our AI processing platform could process satellite imagery live in orbit. Our full tarball, including JARs and an embedded JVM, was ~300MB. When we asked our partners at the satellite company if they could ship this up, they polititely reminded us that they only have a direct link to the satellite once every 90 minutes, and they have a whole lot of things that need to be sent and received from the satellite aside from our software, so it would take roughly 60 days to ship the binaries up for execution.

We had about a week before we wanted to do a press release on our partnership and include some processed images, so I got to work in a parallel pathway trying to build the most minimal MVP of the 1 core image processing workflow in Golang. At the time I’d actually shipped real programs in Go, and I knew it was easy to build and link that.

I wrote a minimal Go program that could connect to some gRPC services already running onboard the satellite, receive and process the images. After compilation, the binary came out to 20MB, with debug and symtab stripping and everything.

This was better than 300MB, but the satellite operator said that 20MB would still take about 3 weeks to transfer.

At that point, I decided to turn to Rust to see just how small I could get the project. In a day or so, I built a simple program leaning on tonic, compiled it to ARM64 (our deployment target was NVIDIA Jetson Xavier AGX devices), and built it with –release and stripped out the symbol table. The resulting program weighed in at around 800KB.

We had a winner! It was a fairly simple program, but it was enough for us to meet the criteria we’d set out for an initial deployment of our software to the satellite.

Obviously this whole situation was contrived: building a demo of deploying software to a space-based device is a bit ridiculous, and this was code that was thrown away (future versions just installed the software on the ground before launch), but it reignited my interest in Rust, and gave me confidence about building non-trivial pieces of software in the language again.

A new chapter⌗

I left my old job to setoff on a new venture, and when my partner and I were looking for a software stack, Java was still my first thought. However, as I looked around, I realized that so much had happened in the Rust ecosystem even in the interceding ~3 years:

- Multiple friends of mine were building their new startups on Rust and were absolutely loving it

- The core language team continued to improve compile times and error messages

- The async-await syntax had been battle-tested in the field, and there were a TON of libraries on crates.io that were making use of tokio and async more generally

- Not just async, but libraries for everything had really exploded, for things like

Rust was quickly becoming one of the richest ecosystems for not just building systems programs, but full-stack applications safely and maintainably.

I gave it another shot, building out the prototype of a server for hosting and specializing open-source LLM models. This required

- A web backend with Postgres connections

- Building a crate to bind with natively compiled GGML

- Logging and telemetry

The project went really well, and there were stumbling blocks but I managed to step over them. If you’re interested, the code is available publicly on GitHub. It’s not the most amazing code but it was a lot of fun building it to learn what writing “modern” Rust is like!

I’m now loving Rust and have used it to write most of my recent code, but there are still things that are missing and that I need to learn more about:

- Observability tooling. I still haven’t found something exactly like

jstackfor getting in-situ threaddumps to understand performance of running applications. - Understanding lifetimes. I’ve actually been able to mostly skirt the need to deeply understand lifetimes. Sometimes the compiler yells at me, and then I add a

.clone()and it gets better. I have not had the need to think deeply about each individual allocation as it’s not been critical for performance, but that’s something I really want to spend more time diving into. - Macros. Most libraries make use of macros as part of their public API, and I suspect that much like getting familiar with Reflect/Codegen in Java was key to unlocking a higher level of building, knowing how to build and use macros is a key part of building great Rust libraries for my team (or should I say, future team).

I think the language, package ecosystem, and community adoption of Rust make now the absolute best time to start building with it, and I’m excited to see where it goes! 🚀